Management of High-Grade T1 Bladder Cancer: Cystectomy versus BCG - Bernard Bochner & Paolo Gontero

June 17, 2020

Biographies:

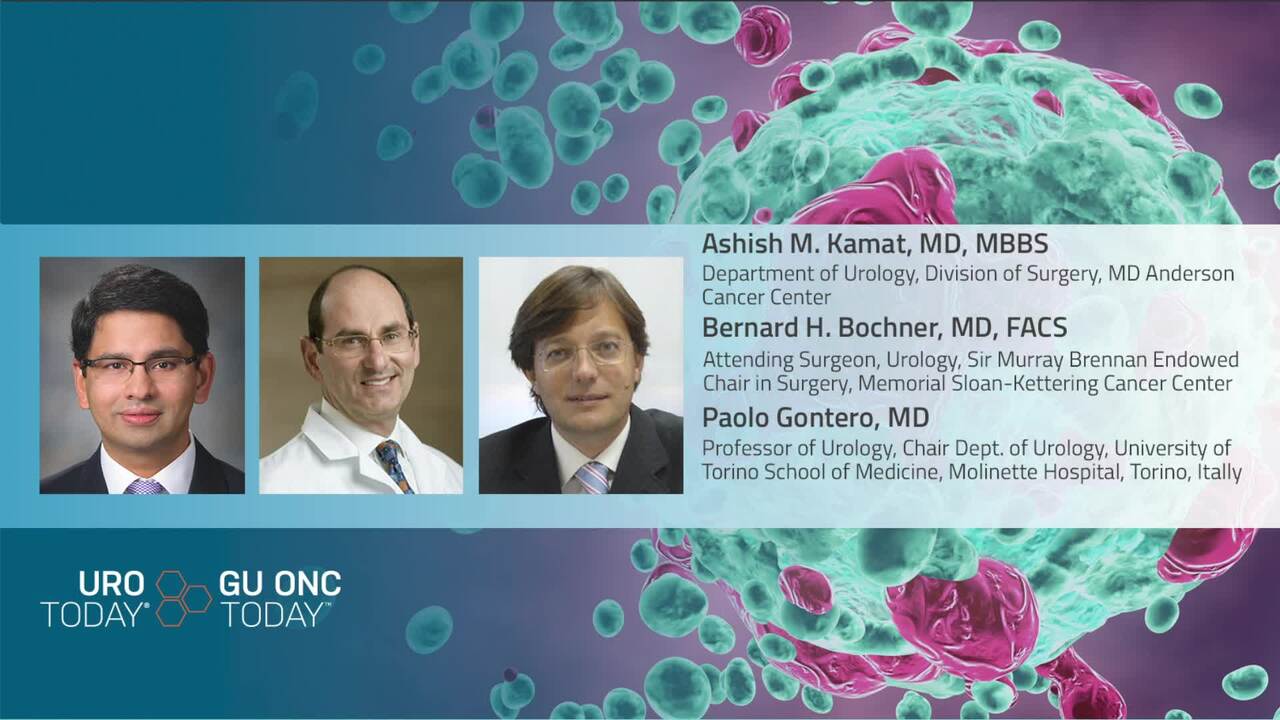

Bernard H. Bochner, MD, FACS, Attending Surgeon, Urology, Sir Murray Brennan Endowed Chair in Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Paolo Gontero, MD, Professor of Urology, Chair, Department of Urology, University of Torino School of Medicine, Molinette Hospital, Torino, Italy

Ashish Kamat, MD, MBBS Professor of Urology and Wayne B. Duddleston Professor of Cancer Research at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

Ashish Kamat: So welcome, everybody. It gives me great pleasure today to welcome two good friends of mine who are also leading experts in bladder cancer. We have from Italy, Dr. Paolo Gontero, who's Chairman of the Division of Urology at the University of Torino School of Medicine. And Dr. Bernie Bochner, who's Attending Surgeon of the Urology Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center here in New York City. Welcome, gentlemen.

So, what we'd like for you to do is consider this hypothetical patient that all of us are constantly being faced with, that has, what a lot of people say is, nonmuscle-invasive or, quote-unquote, "old term superficial disease", but it's T1 disease. So it is not muscle-invasive, but it is T1 disease, which we all know is not the same as CIS or RTA disease, and it's high grade. And if you're faced with this patient, what would you recommend as management? And with that, Dr. Bochner, if you want to take the lead and get started?

Bernard Bochner: Sure. Thank you, Ashish. And good morning to everybody. So, I think one of the first things to remember when we talk about T1 disease, we sort of lump this into a single entity and as all of us know that have been managing this disease for a while, it really isn't. T1 disease could represent a huge spectrum of risk and it's kind of demonstrated on these path slides here. So, on the upper left-hand, you could have a tiny little amount of minimally invasive disease, no surrounding carcinoma in situ, lymphovascular involvement, otherwise considered a low-risk T1 tumor. But a T1 tumor could also represent what we'd have here on the bottom right panel, which is an extensively invasive, large tumor, many times multifocal, with invasion down right up to, but not involving, the muscularis propria. Now, these would all be considered T1 disease, but I don't think it would surprise any of you out there that these clinically do not act the same.

And how do we know that? Well, we know that because we used to treat them all the same. Everybody regardless of whether it was the upper left or the bottom right type of tumor would still undergo a resection, followed by intravesical BCG therapy. And we know from data such as this that they don't act the same, so these are all patients basically treated the same, separated out by the pathology noted on the restaging transurethral resection, which I'm sure we're going to talk about in the discussion. And you could see that that bottom line, the risk of progression is exceedingly high as we get into tumors where even after one good resection, we still find a large amount of invasive [inaudible] present. Again, just in the lamina propria, as opposed to some of these smaller tumors where you go back and you find that you completely resected it with the initial resection. That's the upper left panel.

Those tumors tend to do exceedingly well with BCG. We want to preserve as many of those bladders as possible, but you can see the risk of potentially leaving in some of these higher-risk tumors due to the excessively high risk of progression. We know from, from again, historical treatment of patients, that we used to think that it was okay to allow them even to recur with T1 disease with the thought that, if we get to it at the time it hits the muscle, we'll probably save a lot of these patients. Well, if we allow T1 patients to recur over and over again after intravesical BCG therapy, again, you can see the exceedingly high historical risk of progression. And what this translates to is a very high risk of dying of the disease. So this sort of gets to the point where, well, we could try BCG on some of these higher-risk T1 patients, allow them to continue until it gets into the muscle, that's when it's dangerous. But the reality is, is that many of these patients, we're going to miss the window of opportunity to cure.

And so because of that, now we've changed the way that we manage these patients. We try to select patients who are the upper left panel if you will, the earlier, smaller, minimally invasive type tumors, who we can select for surveillance. And then there's the lower right-hand panel group, the larger multi-focal, more deeply invasive tumors. These are the ones that perhaps we want to offer immediate cystectomy to. Or maybe it's a group in the middle. They're not the smallest, they're not the largest multi-focal. Those we're going to give a try with BCG and at the first sign that they are not responding... So, this is now maybe an earlier trigger when they recur with T1 disease, we go back and we take the bladders out.

When we use this sort of staggered approach, keep the bladders in on the lowest-risk patients, offer immediate cystectomy on the highest-risk patients, and a delayed cystectomy to those patients who are showing early evidence of failure to BCG, now you can see that the cumulative incidence of dying is much lower. Okay? And so with careful selection and aggressive early intervention, we can actually improve the outcome of patients overall.

Ashish Kamat: Thank you Dr. Bochner. Dr. Gontero, the stage is yours.

Paulo Gontero: So, there's no question that T1 high-grade is an aggressive disease. It is not muscle-invasive but is the worst disease among the nonmuscle-invasive. And it's quite staggering that if you look at the literature papers in the last 20 to 30 years, it seems that we have not improved the outcomes. I mean, we still have a 20, 30% of these patients that eventually will die of the disease. And I don't think that the way out to avoid the disease is to treat aggressively all of these patients. These are the results of a very large series and the [inaudible] is retrospective, but these 2500 patients received BCG, and this is the progression curve. And if you see there is only a minority, 25% will have progression and eventually will need the cystectomy, but 75% will keep their bladder. That even in the longterm. So, I think I've seen there that the figures of Bernie and that probably we will have to discuss a little bit.

I was a little bit surprised about this very high-risk of progression in T1 disease. Maybe we are talking about different series. If we compare the results of BCG with the series of patients, this is the old study of Spain and you see the pathological T1 cystectomy. If you look at the long term outcomes, in the end, 20% of these patients will progress and will recur after cystectomy, meaning that there is no cure, they will die of the disease. So we cannot really demonstrate nowadays that there is a dramatic difference between BCG and cystectomy. We have no data. We are a very small, retrospective, series.

But what we have to be very careful, and I agree with Bernie in this respect, if we look in the previous series to those 500 patients who had cystectomy, we have 170 that actually were still T1, high-grade, that had cystectomy and they did quite well. If you can see the five-year survival is 75%. Those who really we need to be aware of are those who are progression before cystectomy or were found to be muscle-invasive at cystectomy because many of these patients are T3 are pathological N1, and I think this is the minority of patients we need to concentrate on. How can we select these patients? That's the key question. I agree. We have a lot of prognostic factors, clinical prognostic factors, variant histology, prostatic, urethral involvement at the eye. We can cluster prognostic factors, put them all together by, we look at the literature. We have only a few studies addressing this and we cannot really derive meaningful information to select the insensitive patient. The pathology of the T1 I think is a matter of discussion because I know there is the view of Memorial, if you have a persistently one disease at which you are, then this is going to be an aggressive disease.

Well, we look at our series and we did not find such a high risk of progression, but I think we can discuss. One of the ways out is going to be in the genome. I think the genome is a very good way to try to identify those patients who are maybe nonmuscle-invasive high-risk, but they actually have the same signatures of muscle-invasive disease. And this is something that has been addressed, for instance, in this study where they actually put together all the databases with all the whole genomic profile and they found that they actually, they could match some normalcy basically that the cancer patient who actually had the same subtypes, molecular subtypes that were typical of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. I think these might be a way out to identify, in my opinion, those not many T1 high-grade that really need to be treated aggressively in the first instance. Thank you very much for your attention.

Ashish Kamat: Thank you. So that was a really, really great discussion from both of you. If I could open the floor and maybe ask you Bernie, what is your discussion paradigm with a patient that presents with T1 high-grade disease; muscle is present, it's not involved, but it's the first time resection. Take us down your pathway of discussion with the patient.

Bernard Bochner: Sure, so restaging resection even in the presence of muscle is still critical for several reasons. As many know, the risk of upstaging even with muscle present on the initial specimen is still a possibility. It may not be a 20 or 30% risk, but there is still at least a 10% likelihood you may find muscle invasion on the re-resection. Additionally, probably about 20 to 25% may still have residual T1 components that need to be resected. If in fact, BCG is going to be offered that is not going to be effectively managed if it's left in place, and an additional 25% of patients will likely have residual TA disease associated, which will also optimally need to be resected in order to make sure that the BCG response is best. So re-resection has lots of potential benefits, not just the potential for identifying an upstaged patient but for cleaning the bladder out if you will, and minimizing the burden of disease that the BCG is going to be required to manage.

So a restaging resection, even if I do the first one, is still something that I routinely recommend. And then basically we have a discussion similar to what we just went through. I still now sort of see T1 patients in three buckets, if you will. The low-risk group of patients who almost routinely or the vast majority are going to do exceedingly well with bladder preservation and BCG with maintenance therapy. The exceedingly high-risk group of patients, the larger multifocal, deeply invasive LVI present, and especially the ones where they have Baron histology such as the micropapillary phenotypes. These are the ones that from a cancer perspective are most likely to benefit from an early, radical cystectomy. And again, now then you've balanced the risk of surgery against all the comorbidities of that patient and the recovery that would be expected. And then there's a group of patients in the middle who, for the most part, we're going to try and give them the benefit of the doubt. Try BCG, watch them carefully and at the first sign that this is not working, so an early recurrence of T1 disease, for instance, those patients we know are at exceedingly high risk for further progression and again, balancing what the patient wants and their comorbidities. It's at that point that a delayed cystectomy would be offered.

And so what we'd like to do is try to get to the point where we see 75% of patients preserving their bladder, that would be fantastic. And take the high-risk players out early. The differences in these outcomes between BCG-treated patients and cystectomy patients, you know, unfortunately, a lot of these historical series, there's a huge amount of selection bias in there. We identify those high-risk patients, and those are the ones that we select for early cystectomy.

When we look at the historical T1 patients with a higher risk of dying of metastatic disease, again, remember, these are the patients who went from T1 to T1 to T1, and maybe at that point were offered cystectomy and we know in that subset of patients that at least 10, 15% of patients may end up metastasizing out. It's why the lymph node-positive rate's gone from 10 to 12% in the historical series down to 1% in the high-risk T1's that we select for cystectomy now as long as they're not including the micro paps.

So you know, again it's a broad-based discussion about risk factors trying to identify those and I totally agree we need better risk stratifications. We don't have any validated molecular markers at this point and we need to work hard in validating some of those because I do think it's going to unlock some of the keys in helping with selection.

Ashish Kamat: Very nice points, Bernie. Paulo, you've done some excellent work that looks at the actual impact of re-TUR. And of course, that's made it into a lot of the guidelines as to, I hate to say selective, but, risk-stratified re-TUR and things like that. Could you enlighten our viewers as to your take on the actual practical relevance of a re-TUR?

Paulo Gontero: Well, I acknowledge that all the guidelines, all the existing guidelines recommend that re-TUR, if you have a T1 disease in the first pathological specimen. And this is something that has not changed at all. And it's also recommended by the European guidelines. From my point of view, if I see a patient because I think that discussion with the patient, your experience is crucial, particularly when we don't have Level I evidence everywhere. So we don't have Level I evidence for re-TUR anyway. So, well we have some Level I evidence, but there are many critical points and there are only studies. So it's difficult to accept there's Level I evidence.

But if I see a patient, when I have done a TUR in the first instance and macroscopically, the tumor was completely removed, the pathologist tells me that there is muscle, a good representation of the muscle in the pathological specimen. Well, I discuss with this patient the possibility to start BCG. If I don't see adverse features, like a tumor in the prostatic urethra, varying pathology where I would be very very careful to give BCG and so I would discuss with the patient the possibility to start. And the first thing starts with the induction course of BCG and then restage the patient at the end of the induction course, making sure that I re-resect the bed and I take multiple biopsies of these patients. I don't think that this approach in a T1 disease, where the muscle was not involved, when you are certain that macroscopically you are quite happy with your work, there was no residual disease. I don't think that this is an approach that cannot be considered from the point of view of the patient.

This is very useful because, proposing a re-TUR for the patient is heavy, it's very hard to have a setback. You're proposing the first instance as a treatment and if BCG will fail at the end of this treatment then you have to strongly consider for this patient a more aggressive treatment. So sometimes I use this approach and that we look over actively to these in a larger series. We look at the patients who had the residual disease at the re-TUR and if the muscle was present in the first instance, actually the re-TUR did impact on recurrence but did not impact on progression and the cancer-specific survival. Meaning that probably this approach could be a set through. But from the point of view of the guidelines, I think it's fair to state that all T1 disease needs to have a re-TUR. It might be simply a question of postponing the re-TUR after the first induction course of BCG.

Ashish Kamat: Thank you. And that's the critical point I wanted to emphasize to our audience that the guidelines clearly all state that a repeat resection is necessary and it is very, very important, no question about it. But a lot of people will often quote you, Paolo, and they will say, "Well in Dr. Gontero's study, he says we did not need to do a repeat resection," and I'm glad you highlighted the point that if you don't do a repeat resection before BCG, you take all those patients back to surgery at the first evaluation and do your repeat resection at that point. So at no point should a T1 high-grade patient have just one TUR and consider that to be the definitive resection. I'm glad you made that point because a lot of people mistakenly quote you and say that one resection is enough, and for T1 high-grade disease, the incidence of under staging today is still as high as 40, 50% in some series, which is clearly too high. And our clinical staging is just not sufficient.

In today's day, you know, with COVID-19 upon us, I would like to ask each one of you if you would modify your treatment paradigm for a patient with T1 high-grade disease. And by that what I mean is, would you be less inclined to offer a re-TUR to decrease the risk of anesthesia or, would you be more inclined to offer BCG and delay re-TUR and conversely, would you change your recommendation for radical cystectomy in these patients even who are at the highest risk category trying to avoid surgery? What are you doing to adapt your practice in the COVID era? And Paulo, if I could have you address this since obviously you're in Italy and you're seeing a lot of this, what modifications have you made?

Paulo Gontero: Recently we had a discussion within the guidelines panel because we had to provide a recommendation from all the treatment options according to the emergency that has led to our COVID disaster. Well, it's a good point because from one point of view you have to reduce the possibility for the patient to come to the hospital. And if you prescribe BCG, the patient will have to do the course and so they'll have to come several times. From the other point of view, there are the risks inherent to having major surgery when you have COVID infections.

Now luckily so far we have not had any problem but, for instance, we had the transplant, the kidney transplant program was fully open and when one patient who is COVID positive, in turn, actually turned to be COVID positive after the transplant and is not doing well. I understand this is patients who have underlying comorbidities, immunosuppression. So, we have to balance these two scenarios. The question is, how do we judge early cystectomy in a T1, very, very high-risk T1 high grade in the COVID era? Should we consider this as a very strong indication for early, early surgery or can we postpone the surgery? And I think this is a very, very difficult question. But, probably balancing everything, I would be more prone to use BCG as a way to postpone surgery.

Ashish Kamat: Bernie, what is your practice, or what have you made any changes in your recommendations taking COVID into account?

Bernard Bochner: So right now in New York we're right in the middle of the surge and peak of the hospital census and we've definitely had to modify how we're managing patients. The operating rooms have essentially been shut down to any elective cases, the majority of urgent cases, and we're only doing just a handful of cancer cases at this point. And so this has been a major issue in dealing with patients, particularly with T1 disease. I would strongly recommend still that patients undergo a restaging TUR because obviously it sets the tone and the proper direction as to treatment. So, if we do find a patient who's upstage to T2 disease and we have to make a quick decision about whether we're going to offer radiation therapy, some sort of bladder preservation as opposed to bringing them into the hospital for a cystectomy. I've had some high-risk T1 patients who probably would be best managed with cystectomy, and up until a couple of weeks ago, I would have recommended that we undergo surgery in that setting.

However, after having an early post-op patient pick up a COVID-19 infection while in the hospital, and this patient got very ill spiking fevers for a good three weeks before they finally turned the corner, managed to stay off the ventilator. It really sort of highlighted the risks of bringing people into the hospital at this point, because of the heavily comorbid patient population that are undergoing cystectomy, we're putting them, I think, at great risk if they end up getting this infection. And so I think I've probably pushed more patients towards BCG therapy to try and buy some additional time. Again, we're balancing the risks of multiple trips into the clinics to end up with BCG instillations, but essentially we're trying to pick the best of two, perhaps not optimal choices for these folks. But I'm trying to keep them out of the hospital at this point until the surge decreases and maybe the risk of picking up the infection will decrease over time.

Ashish Kamat: It's definitely a tough situation that our patients are in right now. You know, to pick the best treatment, but also keeping in mind that their comorbidities put them at a much higher risk of adverse events if they do end up contracting the Coronavirus infection. Well, gentlemen, I do want to thank both of you for taking time off during your busy schedules with everything that's going on. Stay safe. Stay well, and thank you very much for doing this.